STEel cut jewelry

History

Cut steel jewelry is a form of jewelry composed of steel that was popular between the 18th century and the end of the 1930s.[1]

The basic design of cut steel jewelry is a thin metal baseplate onto which closely placed steel studs were riveted.[2]

All manner of jewelry was produced from cut steel: earrings, necklaces, brooches, bracelets, chatelaines, shoe buckles, indeed, even entire parures. In addition, cut-steel frames were popular settings for cameos. Cut-steel’s unique attribute lies in the fact that it was the only fine jewelry imitation in which both gemstone substitutes and their settings were made of the same material; most other faux jewels were composed separately of faux gems and metal settings.[3]

The baseplate could be made from various metals such as brass, tin or silver alloys. Early cut steel consisted of individual steel studs that had been polished and inserted into metal frames. More complicated designs used multiple baseplates held together by small bits of metal. In the early 19th century the manufacturing process shifted towards using stamped strips in place of individual steel studs.[4]

The technique used to create the facets is called chip carving, an ancient technique which traditionally was used on bone and wood. The studs were small and very densely compacted in pavé designs onto a supporting base plate. The idea behind the design was that the polished steel faces would catch the light and sparkle in a similar way to the then highly fashionable diamonds. Aside from the studs some items of cut steel jewelry used highly polished steel chains in their design. Cut steel was combined with precious and semi-precious materials such as jet and pearls.[5]

France served as a major export market but this was interrupted when war broke out 1793. The popularity of cut steel in France may in part have been due to Sumptuary laws which limited who could wear precious metals and diamonds. Manufacture of cut steel within France is attested from 1780 and by the start of the 1820s France had a large amount of domestic production of cut steel.[6]

The quality and use of cut steel jewelry declined throughout the second half of the 19th century with stamped strips replacing individual rivets and pieces becoming increasingly flimsy, the final production ending in the 1930s.

original from National museum collection

Brooch

Designed by: Unknown

Material: Cut steel

Size 14 x 5 cm

Year: 1800

Photo credit:Nationalmuseum

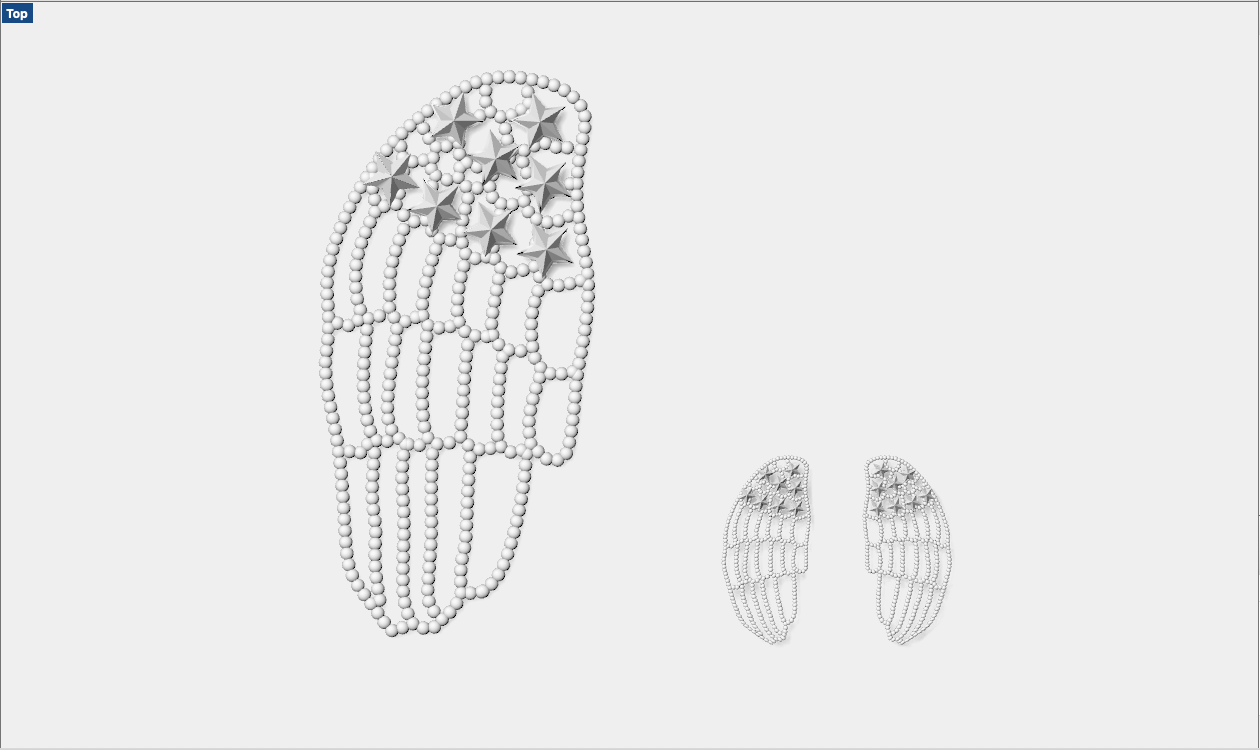

The original brooches that I have chosen from the collection is a pair of identical wing shapes.

It is possible that these brooches are sweat heart wings. The concept of "Sweetheart Wings" has a long-standing tradition. Upon graduating pilot training, servicemen would have a set of their wings turned into a pin or pendant by a local jeweler in order to give to their girlfriend, fiancé, or wife before they went overseas. This custom grew even more popular during World War II, and the handcrafted jewelry became that much more impressive.

re-designed EARRINGS

RE-DESIGN

I have chosen to focus on scale when redesign this wing brooches. Jewelry has a specific scale and level of detail. Historically jewelry has been made of precious materials, this resulted in that jewelry was relatively small. One of the fascinating trades of jewelry is the level of detail that is achieved on these small object.

Todays we can print in a high detail stainless steel. High-grade stainless steel (316L) combines excellent surface quality with great resolution and a significant level of detail. Although it’s not as strong as titanium, it allows for better detail and thinner walls at a much lower price.

Objects printed in 316L stainless steel are created from fine metallic powder primarily composed of iron (66-70%), enriched with chrome (16-18%), nickel (11-14%), and molybdenum (2-3%). The material provides strong resistance against corrosion and is distinguished for its high ductility. These features make it a great candidate for implementation in several industries, such as the medical field for surgical assistance, endoscopic surgery, or orthopedics; in the aerospace industry for producing mechanical parts; in the automobile industry for corrosion-resistant parts; but also, for making watches and jewelry.

316L Stainless Steel printing is very accurate because of the fine coating resolution (30-40 µm) and the laser’s accuracy. Unlike polymer powder sintering, stainless steel printing through DMLS requires adding base structures in order to attach the part to the board and to strengthen distinctive geometries like overhangs. The bases themselves are made from the same powder as the piece and will be taken off afterwards.

With no particular finishing, the material gives off a granular and coarse appearance, though suiting most applications. Smooth and shiny surfaces can be acquired after printing through finishing steps. Pieces can be machined, drilled, welded, electro-eroded, granulated, polished, and coated.

Compared to the other metal 3D printing materials, stainless steel is the smoothest material.

I have chosen to keep the original design of the brooches and just change the scale, from 140 x 50 mm to 40x19mm. High detailed steel has a minimum detail of 0.1mm, this pushes the limits of what when it comes to details. process picture

3d-model of redesign

Footnotes

[1] Hesse, Rayner W. (2007). Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 64–66. ISBN 0313335079.

[2] Clifford, Anne (1971). Cut-Steel and Berlin Iron Jewellery. Adams & Dart. pp. 16–18. ISBN 9780239000699.

[3] https://www.langantiques.com/university/cut-steel-jewelry/

[4] Hesse, Rayner W. (2007). Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 64–66. ISBN 0313335079.

[5] Clifford, Helen (2011). "English ingenuity, French imitation and Spanish desire. The intriguing case of cut steel jewellery from Woodstock, Birmingham and Wolverhampton c.1700-c.1800". L'acier en Europe avant Bessemer. Presses universitaires du Midi. pp. 481–493. ISBN 9782810709793.

[6] Clifford, Anne (1971). Cut-Steel and Berlin Iron Jewellery. Adams & Dart. p. 19. ISBN 9780239000699.

This project was made possible with the support of