CRYSTAL CUT STONE

Faceted stones that catch and reflect light have long captivated the human eye. But when we encounter these dazzling, colorful gems, how can we determine what they truly are? Excluding natural gemstones, we are generally left with three categories: rhinestones, crystals, and paste stones.

Although the terms are often used interchangeably, they refer to different materials and production methods, and vary in value, rarity, and optical quality. Of the three, paste stones are typically the most expensive and rare, primarily due to their historical significance and scarcity. In contrast, modern crystal stones are generally of higher quality—and therefore more costly—than rhinestones.

What differentiates crystal stones from rhinestones is the presence of lead. Crystal is a type of glass that contains lead oxide, which enhances its clarity and refractive index, giving it a brilliance similar to that of genuine gemstones. This is why we encounter the term “lead crystal” in reference to items such as goblets, vases, and ornamental objects. Lead glass is typically composed of 18–40% lead oxide by weight. While the term crystal suggests a crystalline structure, glass is technically an amorphous solid and therefore does not possess a true crystalline lattice. Nonetheless, the historical and commercial use of the term “lead crystal” remains widespread.

The inclusion of lead oxide increases the hardness of the glass, lowers its working temperature and viscosity, and significantly enhances its optical properties—making it ideal for imitation gemstones. In fact, glass has been used to imitate nearly every type of gemstone throughout history. Glass gem imitations date as far back as 1500 AD. During the 11th century, their popularity prompted regulatory intervention by the French goldsmiths’ guild, which stipulated that gold should be reserved for natural gemstones, while silver should be used for glass gems, as a way of distinguishing between the two.

Before the 17th century, glass was typically molded rather than faceted, and thus lacked the sparkle associated with cut gemstones. Rock crystal, a naturally occurring form of quartz, was often preferred for imitations because it could be polished and faceted, offering greater brilliance.

A major advancement in glass-based jewelry came in 1724, when French jeweler Georges Frédéric Strass invented a form of leaded glass that could be cut and polished using metal powders to simulate the appearance of diamonds. His innovation, known as white “diamante” or “strass”, gained popularity among the Parisian elite. The rise of evening social events lit by candlelight created a demand for reflective, sparkling stones, further fueling the popularity of paste and crystal stones.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, paste stones remained a fashionable and widely accepted alternative to precious gems. In 1840, a new method was developed for permanently foiling paste stones, enhancing their brilliance. Paste stones from this period often featured a small black spot on the culet, a design choice intended to mimic the optical properties of a diamond’s cut.

One of the most well-known producers of precision-cut crystal stones is Swarovski. In 1892, Daniel Swarovski revolutionized the industry by inventing a mechanical cutting machine capable of producing highly refined and symmetrical stones. His innovation led to the creation of Swarovski crystals, which are still recognized for their brilliance and quality today.

original from National museum collection

garniture

Designed by: Unknown

Material: Silver-plated metal, silver, crystal glass

Size: 16 cm

Year: second half of the 19th century

garniture

This necklace and bracelet, made of silver and glass, are part of a granityr—a term derived from the French garniture, meaning 'accessory' or 'ornament'. In the context of arts and crafts, a garniture refers to a set of coordinated decorative objects, typically sharing a common aesthetic or formal language.

These pieces date from the second half of the 20th century and exhibit a classical, minimalist design characteristic of that period. At the time, genuine gemstones of such size were prohibitively expensive and accessible only to the wealthy. The introduction of crystal stones onto the market significantly expanded the availability of jewelry featuring large, eye-catching stones. This innovation democratized access to ornamental jewelry, allowing a broader public to enjoy designs that were previously reserved for an elite clientele.

The design of these pieces reflects a shift toward simplicity, where minimal forms serve to emphasize the stone’s visual and reflective qualities. The uniformity in the size and cut of the stones suggests that the maker intended to make a singular aesthetic statement. The focus is placed entirely on the luster and brilliance of the stones, with the metalwork functioning primarily as a subtle frame to enhance their radiance.

re-designed NECKLACE

RE-DESIGN

In this project, I have chosen to work with watermelon quartz. “Quartz” is a widely used—and generally legitimate—term in the bead and jewelry industry. While natural quartz is abundant globally and exists in a wide range of types, the term is sometimes misused by less reputable vendors as a generic label for any clear or translucent material. [3]

Genuine quartz often contains small inclusions, and while some stones are naturally occurring, it is common for them to be modified in some way to enhance their luster or color. Watermelon quartz is one of the most visually striking varieties, characterized by its trigonal crystal structure and a vibrant combination of pink, green, and white hues within a single crystal. It is this vivid blend of colors that gives the stone its distinctive name.

Just as crystal stones are manmade—produced through the combination of lead and glass—watermelon quartz is frequently altered by human intervention to intensify its color. To highlight the unique qualities of these stones, I have chosen to use a setting that allows for significant light penetration. This design choice enhances the stone’s ability to reflect light, particularly through its darker tones, giving it the visual presence it deserves.process picture

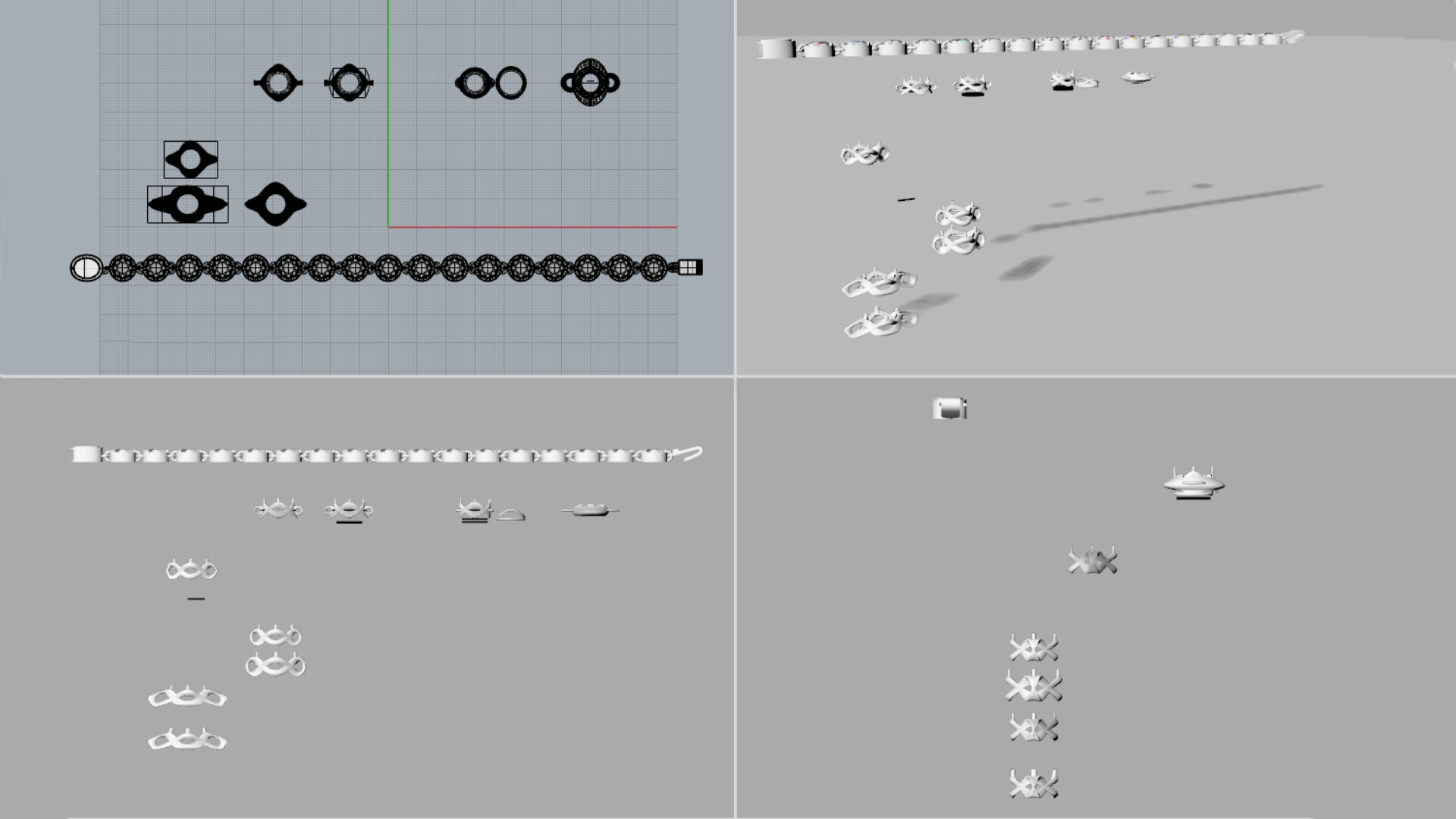

3d-model of redesign

Footnotes

[1] Benvenuto, Mark Anthony (24 February 2015). Industrial Chemistry: For Advanced Students. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110351705.

[2] https://navettejewellery.org/2017/05/29/history-of-imitation-gemstones-paste-and-glass-gemstones/

[3] https://bluedoorbeads.wordpress.com/tag/watermelon-quartz/

This project was made possible with the support of